June 19th

Jameson F. – In Archeologies of the Future

Growing up in postwar Germany, I did not see Ernst Bloch’s visions of a future world so much as utopian, but rather as a search for a possible, new society of the future. Bloch wrote his ‘Prinzip Hoffnung’ in exile during WWII and after the war in the newly established GDR, the socialist, Eastern-Germany, the German Democratic Republic. It was the time after the war when people started to understand the devastating impact the fascist regime had had on the world and on their country, a time where everything was lost, the time of no words and incredible guilt in Germany where the worst things had happened and a new society needed to be built. Growing up in Western Germany, as young adults and students at the beginning of the 80th, I remember we were discussing Bloch’s interpretation of Marx and ideas of a possible structure for a humanistic society without oppression and exploitation. Shockingly however, Bloch supported the Stalinistic ‘cleansings’ which happened in Russia under the reign of Stalin, a time during which millions of political opponents were killed. The perfect society where people are all equal and non-political without any oppression and exploitation only exists on the paper. In that context Marcuse’s ideas were obviously discussed as well.

Anti-Utopia and Dystopia: Rethinking the Generic Field

An incredible overview of films and books that describe Utopias and Dystopias, divided into 10 categories. While I read some of the books and saw some of the movies mentioned, I must admit that many of the authors mentioned are unfamiliar.

Foucault created the term heterotopia to talk about the ‘different’ space. While an utopia is an idea that represent a perfect vision of society where everything is good and in a dystopia everything is bad, heterotopia is where things are different.

Anti-Utopia and Dystopia: Rethinking the Generic Field

Anti-utopia / dystopia categories:

Utopia: good life / society; no conflict.

Critical Utopias: 90s; utopia with faults; denial of utopian impulses, exploitation / domination.

Critical negation: “metapolitical” —corporate domination of “no alternative” — no Utopian future.

Critical dystopia: evaluations superficial; pessimism; hybrids of realism.

PostUtopian: justice, freedom / democracy.

June 18th

Architectural Dystopian Projections in the films Metropolis, Brazil and the Island.

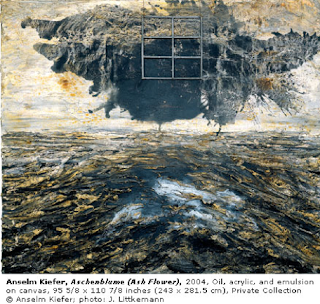

I am currently discussing dystopias and utopias in contemporary painting and was just discussing artists like Michael Andrews (Dystopias) and Makiko Kudo (Utopias).

Movies like the Blade Runner and the Hunger Games come to mind too.

Metropolis, Brazil and The Island, are exemplified architectural environments, the ideological basis for the dystopian visions to comment on utopia as a vehicle bankrupts personal expression, multiplicity and difference, essential elements of life as well as of creative expression, interests of the majority in the name of equality and justice through its uniformity, determinism.

Utopians forget that society is a “living organism” (Maria Luise Bernieri), imposing paternalistic monomania. Dsytopian fiction films demand organic flexibility and adaptability to social and political constructs. Supposedly, material and technological innovations will abolish valued ways of living.

Dystopian influences in the 19thcentury were symbolised by the faith in the machine and in the late 20thcentury were symbolized by the faith in digital technology, later in biotechnology.

Utopia has always been a political issue, an unusual destiny for a literary form: yet just as the literary value of the form is subject to permanent doubt, so also its political status is structurally ambiguous. The fluctuations of its historical context do nothing to resolve this variability, which is also not a mater of taste or individual judgement.

June 25thand July 6th

Utopia and modern architecture

An utopic vision allows us to make ourselves free and think about what would be right or ideal instead of planning into the future from today and working with the politics and the given facts of today. Of course, new architecture cannot disconnect itself from the now and of course architects have to make compromises. Obviously economics and development policies limit the capacity of architecture to be utopian. The planning for an utopia cannot start with architecture, it would need to start with a planning of a different society. Architecture can only be a part of it.

June 27th

The Story of Utopia, by Lewis Mumford Chapter 9, 4-5

When I read sentences like ‘work is given freely and the proceeds of work exchanged freely’, or ‘as far as man can be satisfied and happy in a good environment, this community is satisfied and happy’ I was reminded of a documentation I saw recently about the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh cult and their years in Oregon in the US. They established Rajneeshpuram in 1981, but due to many legal issues Bhagwan left about 1985 and the place was abandoned. An incredibly interesting story though, with thousands of people following their guru and wanting to establish a utopic place of happiness together.

June 29th

It is more than understandable that an utopian impulse, with the idea of planning ideal cities and societies came up during the time of the European encounter with the Americas. While this new world seemed to offer the potential of creating perfect cities and places, in today’s world and reality a realistic development of a new society would look very different.

More than 65 million people are refugees at the moment, people who have to leave everything behind hoping to find a place to live and take refuge. Every place on earth will be impacted by global warming. Societies need to go back and simplify life, not waste energy and pollute the planet. The energy will need to come from the wind and the sun, there can’t be plastic pollution anymore. The oceans will need to be cleaned. Resources will come to an end and a realistic dream of a perfect new world would probably talk about small socialist communities in which everybody has his chores and where everything to eat is cultivated. The diet would come merely from the local area. Globalization was the biggest mistake of human society, the rich got richer and the poor countries are being exploited and polluted more.

June 26thand July 10th,11th

M. Tafuri

In Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development, 2. Form as Regressive Utopia

Cities (Piranesi: “absurd machine”) through industrialization, bourgeois post 18c, lost its urban dimension. Eclecticism, technological progress produced open structured cities that sought utopian solutions. Urban morphology combined rational / irrational ideology; ambiguity: critical value. Through commercialism, the city lost authenticity.

Art lost coherence of forms.

Marxist criticism diminished bourgeoise ethics. Social utopianism became profit acquisition.

Mid 19c – 1931: Art avantgarde individualization addresses “unsatisfied needs”. Architectural ideology becomes “ideology of the plan”, supplanted after 1929 by national capital reorganisation.

“Utopia as a project.”

19th c “. Utopian Weimar domination. Ideology became utopia; intellectual work, “unproductive.”

Nietzsche: freedom from value, an impediment. Science is “self-control”, able to evaluate reality.

Wertfreiheit: the irrational Is negative, inseparable from the positive (capitalist vs working class work). Rational future eliminates risk.

Mannheim: utopia was realizable. Revolutionary moment: utopia. Conservative thought must be criticized.

Utopia: rational project. Negative utopia is rejected, political control becomes scientific evaluation.

Relations between intellectual, capitalism, avant-garde social behaviour transformed traditional ideology into utopia, global rationalization.

Post 1917 Utopia becomes extinct. Capitalism contradictions exist (Europe, America). 1920s: The avant-guard as social redemptionists, political interventionists.

Intellectuals, artists manipulated: “historic tasks’, ideology production. Both help to recover Totality. Democratic capitalism: (Germany 1918-1921). Voluntary domination is achieved.

Obstacles to prejudices allow human mythology – cynical and regressive mythology, serve to break only weak resistance.

Utopia as a political issue is considered structurally ambiguous. Historical contexts, taste and judgement cannot resolve this.

Stalinism, synonymous with Utopia betrayed humanity. Ideal purity, the perfect system was domination, identified with aesthetic modernism, counterrevolutionary; the political right lost interest. “Difference”, became an anti-state, anarchist, centralizing, authoritarian (Marxism influence). Bolsheviks denounced Utopian concepts. Socialism and Utopia relationships are still unresolved. The “post-globalization Left” exists because communist and socialist parties are discredited. The emergent world market consolidation will allow new forms of political agency.

Stalinism, synonymous with Utopia betrayed humanity. Ideal purity, the perfect system was domination, identified with aesthetic modernism, counterrevolutionary; the political right lost interest. “Difference”, became an anti-state, anarchist, centralizing, authoritarian (Marxism influence). Bolsheviks denounced Utopian concepts. Socialism and Utopia relationships are still unresolved. The “post-globalization Left” exists because communist and socialist parties are discredited. The emergent world market consolidation will allow new forms of political agency.

June 17th

June 22nd and July 7th

Introduction : Utopia Now

Very interesting was Marcuse’s annunciation of the end of utopia. Utopia was not utopic anymore with the realization that at any time humans could ‘make the world into hell’ . This is from his lecture in Berlin

Ich muß zunächst mit einer Binsenwahrheit anfangen, ich meine damit, daß heute jede Form der Lebenswelt, jede Verwandlung der technischen und der natürlichen Umwelt eine reale Möglichkeit ist und daß ihr Topos ein geschichtlicher ist. Wir können heute die Welt zur Hölle machen, wir sind auf dem besten Wege dazu, wie Sie wissen. Wir können sie auch in das Gegenteil verwandeln. Dieses Ende der Utopie, das heißt die Widerlegung jener Ideen und Theorien, denen der Begriff der Utopie zur Denunziation von geschichtlich-gesellschaftlichen Möglichkeiten gedient hat, kann nun auch in einem sehr bestimmten Sinn als »Ende der Geschichte« gefaßt werden, nämlich in dem Sinne, daß die neuen Möglichkeiten einer menschlichen Gesellschaft und ihrer Umwelt, daß diese neuen Möglichkeiten nicht mehr als Fortsetzung der alten, nicht mehr im selben historischen Kontinuum vorgestellt werden können, daß sie vielmehr einen Bruch mit dem geschichtlichen Kontinuum voraussetzen, jene qualitative Differenzen zwischen einer freien Gesellschaft und den noch unfreien Gesellschaften, die nach Marx in der Tat alle bisherige Geschichte zur Vorgeschichte der Menschheit macht.

In this chapter, utopia is envisioned through the hypothetic dream state of William Morris, in England’s Thames Valley.

The protagonist transports to a world without landmarks where grass covers irretrievable ruins. A collector that values money, he as a “guest” in a “Guest House”, where the community administers to his needs. The community members are of optimal health available through “busy work.” Other guests are crafts people, workers. Because of simplified standard of living, release from the pressure of artificially stimulated wants, making a living is uncomplicated and easily performed, done in pleasant conditions. Handicrafts, manual skills are valued above technology. Industry produced goods are in disuse. Simplicity through making, an immediacy, direct supply and interchange of goods out of local production replace commodity exchange of the earlier imperialistic world.

Community concentrations are architecture, arts. Most people are neither scholars nor scientists.

Big cities have disappeared. London is now rural. Although shops exist, no money is involved. Ideal common halls are community convening places for eating, conversation. Economic pressure is absent. Leisure is dignified, also known as the life of the artist. The instinct of workmanship, the creative impulse creates comradeship, beauty.

Chapter 10, Mumford, July 5th

The English Country House culture is considered an utopia. Its history, drawbacks are noted through literary references.

Originally an aristocratic institution, it’s culture is now widespread. Contrary to Plato’s desirable good community, its perpetuation is aimed at owners’ happiness, based on privilege, not work. Power, wealth is required for its exclusive and limitless possession, passive enjoyment in multiple houses.

Historically, force and fraud obtained ownership. Therefore, no congenial associations existed between neighbours, communities and houses /owners. Functionaries administered to this utopia, a desirable vacuity.

Literature and fine arts flourished but as monetary objects, not creative elements in communities. A corrupting influence, object features are derivative, stolen, purchased or basely copied. Culture came to mean not participation in creative activities but acquisition.

The Utopian Impulse

The “utopian impulse” is rooted in Plato, Herodotus and Vesuvius. “Utopia” was coined by T. More (16th c). “Rebirth” of ancient ideas throughout the Italian Renaissance included city / society planning, a humanistic interest through Europe. Because of “New World” settlements, creation of ideal communities with religious freedom seemed possible.

Renaissance architects utilised Plato’s physical / ethical ideal society and Vitruvius’ perfect geometric shapes as universal order, designed based on patterns of human proportion and harmonious geometric order to give structure physically and morally harmonious society.

Thomas More wrote “Utopia” (1516) about socio‐political reform through a fictionalize society. Translations of Utopiawere adjusted to fit different cultures and societies.